how to find removable discontinuity

"Jump point" redirects here. For the science-fiction concept, see Hyperspace.

Continuous functions are of utmost importance in mathematics, functions and applications. However, not all functions are continuous. If a function is not continuous at a point in its domain, one says that it has a discontinuity there. The set of all points of discontinuity of a function may be a discrete set, a dense set, or even the entire domain of the function. This article describes the classification of discontinuities in the simplest case of functions of a single real variable taking real values.

The oscillation of a function at a point quantifies these discontinuities as follows:

- in a removable discontinuity, the distance that the value of the function is off by is the oscillation;

- in a jump discontinuity, the size of the jump is the oscillation (assuming that the value at the point lies between these limits of the two sides);

- in an essential discontinuity, oscillation measures the failure of a limit to exist; the limit is constant.

A special case is if the function diverges to infinity or minus infinity, in which case the oscillation is not defined (in the extended real numbers, this is a removable discontinuity).

Classification [edit]

For each of the following, consider a real valued function f of a real variable x , defined in a neighborhood of the point x 0 at which f is discontinuous.

Removable discontinuity [edit]

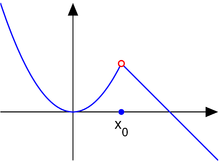

The function in example 1, a removable discontinuity

Consider the piecewise function

The point x 0 = 1 is a removable discontinuity. For this kind of discontinuity:

The one-sided limit from the negative direction:

and the one-sided limit from the positive direction:

at x 0 both exist, are finite, and are equal to L = L − = L + . In other words, since the two one-sided limits exist and are equal, the limit L of f(x) as x approaches x 0 exists and is equal to this same value. If the actual value of f(x 0) is not equal to L , then x 0 is called a removable discontinuity. This discontinuity can be removed to make f continuous at x 0 , or more precisely, the function

is continuous at x = x 0 .

The term removable discontinuity is sometimes broadened to include a removable singularity, in which the limits in both directions exist and are equal, while the function is undefined at the point x 0 .[a] This use is an abuse of terminology because continuity and discontinuity of a function are concepts defined only for points in the function's domain.

Jump discontinuity [edit]

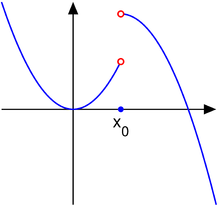

The function in example 2, a jump discontinuity

Consider the function

Then, the point x 0 = 1 is a jump discontinuity.

In this case, a single limit does not exist because the one-sided limits, L − and L + , exist and are finite, but are not equal: since, L − ≠ L + , the limit L does not exist. Then, x 0 is called a jump discontinuity, step discontinuity, or discontinuity of the first kind. For this type of discontinuity, the function f may have any value at x 0 .

Essential discontinuity [edit]

The function in example 3, an essential discontinuity

For an essential discontinuity, at least one of the two one-sided limits doesn't exist. Consider the function

Then, the point is an essential discontinuity.

In this example, both and don't exist, thus satisfying the condition of essential discontinuity. So x 0 is an essential discontinuity, infinite discontinuity, or discontinuity of the second kind. (This is distinct from an essential singularity, which is often used when studying functions of complex variables).

Supposing that is a function defined on an interval , we will denote by the set of all discontinuities of on . By we will mean the set of all such that has a removable discontinuity at . Analogously by we denote the set constituted by all such that has a jump discontinuity at . The set of all such that has an essential discontinuity at will be denoted by . Of course that

Counting discontinuities of a function [edit]

The two following properties of the set are relevant in the literature.

- The set of is an F σ set. The set of points at which a function is continuous is always a G δ set (see[2]).

Tom Apostol[3] follows partially the above classification by considering only removal and jump discontinuities. His objective is to study the discontinuities of monotone functions, mainly to prove Froda's theoremm. With the same purpose, Walter Rudin[4] and Karl R. Stromberg[5] study also removal and jump discontinuities by using different terminologies. However, furtherly, both authors state that is always a countable set (see[6] [7]).

The term essential discontinuity seems to have been introduced by John Klippert[8]. He then subdivides the set E into the three following sets:

and don't exist ,

exists and doesn't exist ,

doesn't exist and exists .

Of course . Whenever , is called an essential discontinuity of first kind. For any it will be said an essential discontinuity of second kind. Hence the following important property is proved:

- The set is countable.

Rewriting Lebesgue's Theorem [edit]

When and f is a bounded function it is well-known the importance of the set in the regard of the Riemann integrability of f . In fact, Lebesgue's Theorem (also named Lebesgue-Vitali theorem) states that f is Riemann integrable on if and only if is a set with Lebesgue's measure zero.

In this theorem seems that all type of discontinuities have the same weight on the obstruction that a bounded function f be Riemann integrable on . Since countable sets are sets of Lebesgue's measure zero and a countable union of sets with Lebesgue's measure zero is still a set of Lebesgue's mesure zero, we are seeing now that this is not the case. In fact, the discontinuities in the set are absolutly neutral in the regard of the Riemann integrability of f . The main discontinuities for that purpose are the essential discontinuities of first kind and consequently the Lebesgue-Vitali theorem can be rewritten as follows:

The case where correspond to the following wellknown classical complementary situations of Riemann integrability of a bounded function :

- If f has right-hand limit at each point of then f is Riemann integrable on (see [9])

- If f has left-hand limit at each point of then f is Riemann integrable on

- If f is a regulated function on then f is Riemann integrable on .

Examples [edit]

Thomae's function is discontinuous at every non-zero rational point, but continuous at every irrational point. One easily sees that those discontinuities are all essential of the first kind, that is . By the first paragraph, there does not exist a function that is continuous at every rational point, but discontinuous at every irrational point.

The indicator function of the rationals, also known as the Dirichlet function, is discontinuous everywhere. These discontinuities are all essential of the first kind too.

Consider now the ternary Cantor set and its indicator (or characteristic) function

Recall that is given by

where the sets are obtained by recorrence according to

In view of the discontinuities of the function , let's assume a point .

Therefore there exists a set , used in the formulation of , which does not contain . That is, belongs to one of the open intervals which were removed in the construction of . This way, has a neighbourhood with no points of , where by consequence only assumes the value zero. Hence is continuous in . This means that the set of all discontinuities of on the interval is a subset of . Since is a noncountable set with null Lebesgue measure, also is a null Lebesgue measure set and so in the regard of Lebesgue-Vitali theorem is a Riemann integrable function.

More precisely one has . In fact, if , no neighbourhood, , of can be contained in . Otherwise we should have, for every , , which is absurd. since eachone of these sets is composed by interval with length , which does not allow that inclusion for values of sufficiently large in manner that . This way any neighbourhood of contains points of and points which are not of . In terms of the function this means that both and don´t exist. That is, , where by , as before, we denote the set of all essential discontinuities of first kind of the function . Clearly

See also [edit]

- Removable singularity

- Mathematical singularity

- Extension by continuity

- Smoothness

- Geometric continuity

- Parametric continuity

Notes [edit]

- ^ See, for example, the last sentence in the definition given at Mathwords.[1]

References [edit]

- ^ "Mathwords: Removable Discontinuity".

- ^ Stromberg, Karl R. (2015). An Introduction to Classical Real Analysis. U.S.A.: American Mathematical Society. pp. 120. Ex. 3. ISBN978-1-4704-2544-9.

- ^ Apostol, Tom (1974). Mathematical Analysis (second edition). Addison and Wesley. pp. 92, sec. 4.22, sec. 4.23 and Ex. 4.63. ISBN0-201-00288-4.

- ^ Walter, Rudin (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis (third edition). McGraw-Hill. pp. 94, Def. 4.26, Thm 4.30. ISBN0-07-Y85613-3.

- ^ Stromberg, Karl R,. Op. cit. pp. 128, Def. 3.87, Thm. 3.90. CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- ^ Walter, Rudin. Op. cit. pp. 100, Ex. 17.

- ^ Stromberg, Karl R. Op. cit. pp. 131, Ex. 3.

- ^ Klippert, John (February 1989). "Advanced Advanced Calculus: Counting the Discontinuities of a Real-Valued Function with Interval Domain". Mathematics Magazine. 62: 43–48 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Metzler, R. C. (1971). "On Riemann Integrability". American Mathematical Monthly. 78 (10): 1129–1131.

Sources [edit]

- Malik, S.C.; Arora, Savita (1992). Mathematical Analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN0-470-21858-4.

External links [edit]

- "Discontinuous". PlanetMath.

- "Discontinuity" by Ed Pegg, Jr., The Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Discontinuity". MathWorld.

- Kudryavtsev, L.D. (2001) [1994], "Discontinuity point", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

how to find removable discontinuity

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classification_of_discontinuities

Posted by: hunteredwasind.blogspot.com

![I=[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d6214bb3ce7f00e496c0706edd1464ac60b73b5)

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

![{\displaystyle f:[a,b]\rightarrow \mathbb {R} }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fc0d2d0b70573525d149ab82948308455d1853d0)

![]a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/784ada3a213049f80d0909d4b95b4b8a7f871e83)

![{\displaystyle [a,b].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3ba5cb29655f824ce80a0b6a32d9326d0e8742cd)

![{\displaystyle {\mathcal {C}}\subset [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8aaa630e6658df0560ae1e76d3ffa0830927d124)

![{\displaystyle \mathbf {1} _{\mathcal {C}}(x)={\begin{cases}1&x\in {\mathcal {C}}\\0&x\notin [0,1]\setminus {\mathcal {C}}.\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0c35a088d096fa95271ac0783526cb5e317a31b3)

![{\displaystyle C_{n}={\frac {C_{n-1}}{3}}\cup \left({\frac {2}{3}}+{\frac {C_{n-1}}{3}}\right){\text{ for }}n\geq 1,{\text{ and }}C_{0}=[0,1].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/63ce55f16d75e2f4e4541e0f591116f23de19dc3)

![[0,1]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/738f7d23bb2d9642bab520020873cccbef49768d)

0 Response to "how to find removable discontinuity"

Post a Comment